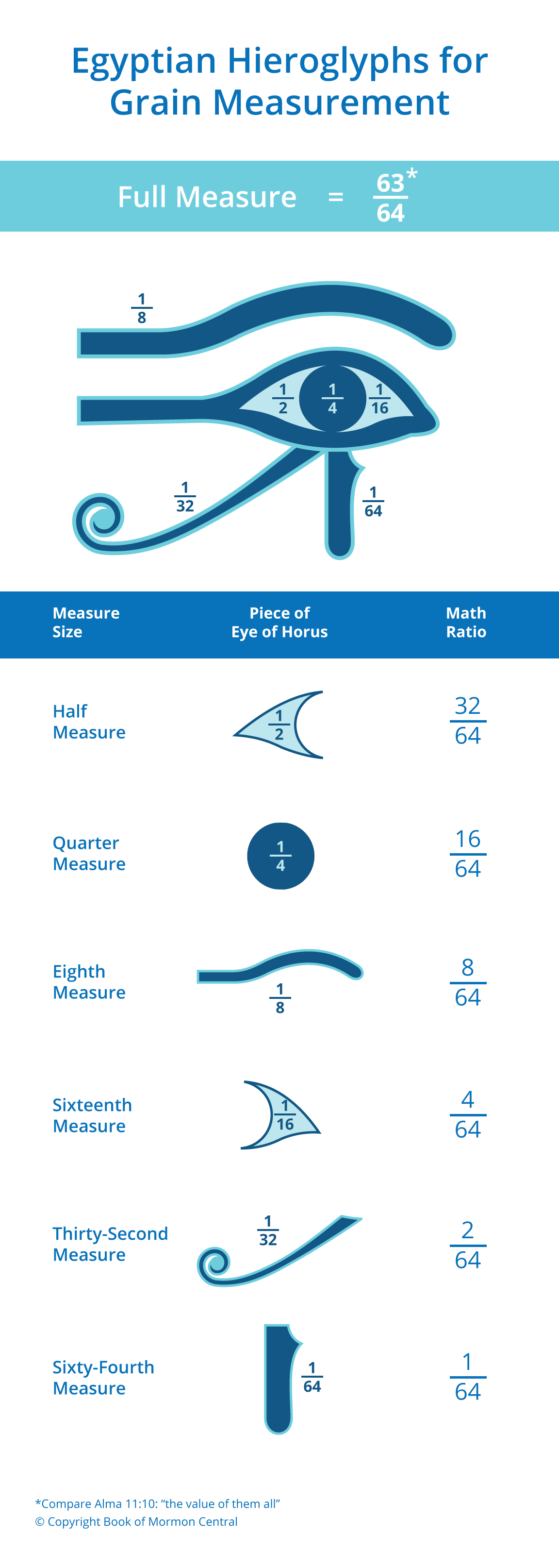

Where did Mosiah’s system of weights and measures come from? We aren’t told, but we do know from Mosiah 1:2–5 that King Benjamin taught his sons "in all the language of his fathers," including "the language of the Egyptians," so that they could read the engravings on the plates of brass. No doubt, one of the first things Mosiah and his brothers would have learned was how to count in Egyptian, a basic part of any language. In the early twentieth century, a mathematical papyrus was found that shows us how precise and elegant the ancient Egyptian system of weights and measures actually was. Interestingly, the mathematical symbols for counting in the marketplace were all related to the "wedjat eye," or the right eye of Horus. Altogether, it was a symbol of protection, royal power, and complete good health, as well as a full measure of grain. When broken into its parts, moving around the eye, each part became the glyph that represented that fraction of the full measure. So, the pupil was 1/4;, the eyebrow was 1/8, the eyelash was 1/32, and the tear duct was (sadly) only 1/64. This system was binary (each measure was half the size of the previous measure), and there were six of these weights or measures with the seventh being the sum of them all, just like the system inaugurated by King Mosiah (Figure 1).

Moreover, in the beginning of legal history in Mesopotamia, a king named Eshnunna (1770 B.C., just before Hammurabi) set forth a body of laws. His law code began, as its first matter of business, by establishing how much silver was worth how much barley, and then how much silver it took to purchase how much sesame, and so forth. This was an immense step forward in establishing a kingdom-wide economy with regulated ratios and established proportions. These laws in the kingdom of Eshnunna allowed people to deal confidently in the marketplace with barley, silver, oil, lard, wool, salt, bitumen, and refined and unrefined copper. And this was one more thing that King Mosiah’s system also did, allowing people to convert between precious metals and "every kind of grain" (11:7).

Figure 1 John W. Welch and Greg Welch, "Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Grain Measurement," in Charting the Book of Mormon, chart 113.

This was an early form of price regulation, so that people could not overcharge. They also could not create artificial scarcity on a commodity like corn in order to price gouge. It was a big step forward in creating a viable market economy, but at the same time it could also be subject to abuse, as is seen with the lawyers and judges of Ammonihah.

By combining the binary aspect of the Egyptian grain measure with the commodities conversion feature found in the earliest Mesopotamian laws, Mosiah (perhaps unwittingly, but maybe intentionally) brought together cultural contributions from both the Nephite (Egyptian) and the Mulekite (Near Eastern, Jaredite, and Mesopotamian) worlds. And recent interest in the complex and long-term use of standardized accounting practices and currencies in the ancient Maya world offers students of the Book of Mormon yet another glimpse into why the details about Mosiah system of weights and measures were reported as they were in the book of Alma.

Book of Mormon Central, "Why You Should Care About the Nephite Weights and Measures System (Alma 11:7)," KnoWhy 322 (June 5, 2017).

John W. Welch, "The Laws of Eshnunna and Nephite Economics," in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 147–149.

Kirk Magleby, "Money in Ancient America," online at bookofmormonresources.com. This blog post draws extensively from David A. Freidel, Marilyn A. Masson, and Michelle Rich, "Imagining a Complex Maya Political Economcy: Counting Tokens and Currencies in Image, Text and the Archaeological Record," Cambridge Archeological Journal (2016), 29–54.